Belief in Magic in Shakespeare, Rohmer, and Plato

Harun Ćurak, 2023

The Threat of Skepticism

Throughout Cities of Words, Stanley Cavell repeatedly identifies the problem of skepticism as a threat to the vision of moral perfectionism – the quest for an unattained but attainable self. On this journey, our propensity to look for epistemological assurance about our existence – along with the existence of others and the external world – is pervasive, incapacitating, and often destructive. For Cavell, it is precisely this skeptical impulse that causes problems on several levels of inquiry, across several films: Gregory’s insane behavior in Gaslight; the xenophobia that the courtroom exhibits toward Mr. Deeds in Mr. Deeds Goes to Town; and, perhaps most importantly – the reservations we, as readers, feel when faced with Cavell’s strong claims about a film’s independent philosophical voice. Considering the frequency and power with which the skeptical problem rears its head, it might be surprising to find that Cavell speaks less systematically about how one might solve it or respond to it. Partly, this is because skepticism is a broad denotation for a disease whose symptoms are as varied as the lives which it affects. Yet if, in a Wittgensteinian mode of thought, we are to “treat a [philosophical] problem; like an illness,” it must be worth considering what remedies are at our disposal.

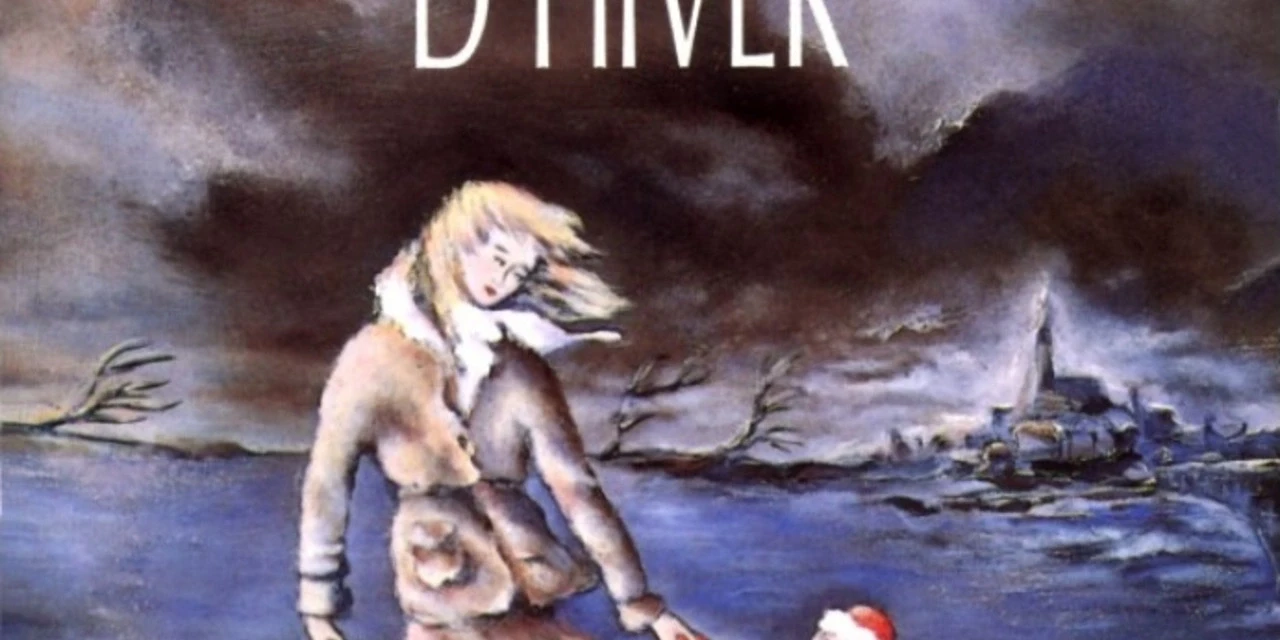

As a start, it seems that one of the most promising candidates is faith, an idea Cavell engages with most explicitly in his reflections on Rohmer’s The Winter’s Tale & Shakespeare’s A Tale of Winter. Just as one might expect of skepticism, faith is problematized on two levels: the first level of inquiry concerns the faith the depicted characters have in the unknown, call it faith in the attainability of their unattained self or society; and second, the issue of faith as it relates to belief in magic (representing film and theater), of seeing this belief as a carrier of genuinely transformative philosophical value. The latter issue provides a natural link to Cavell’s chapters on Plato’s Republic and His Girl Friday, wherein the issue of rationality versus magic is raised rather explicitly. This essay will concern itself with providing a positive account of what, in a perfectionist context, faith means. Our initial problems therefore take shape: In a perfectionist context, can faith have rational grounding? Must it? What is the significance of faith, understood as a belief in something without rational grounding, to the project of moral perfectionism?

Skepticism and Ordinary Language

To begin looking for an answer, it is worth reconstructing the relationship Cavell sees between skepticism and ordinary language. Philosophers, from Descartes to Kant and beyond, have been at pains to answer the skeptical challenge about the truth of one’s/others’/the world’s existence. Yet, the threat always reappears, tailored and stronger than before. For a philosopher like Cavell, this is a sign that the dialectic is somehow rigged in the skeptic’s favor. The subsequent recommendation is to reorient the investigation in order to analyze how skepticism subverts our knowledge. Following Wittgensteinian thought, Cavell thinks that the skeptical impulse comes from trusting our far-less-than-perfect ordinary language to give us impossibly perfect answers. Because of this, Cavell notes that “skepticism contrasts with what, in reaction to the skeptical threat, we can see as ordinary or everyday life;” and, since we “must find a way to put this doubt aside,” we must commit ourselves to the ordinary. In the context of philosophical debate, this commitment means that we must learn to have faith in the limits of our language, which is to say, be satisfied with the limits of what we can know. This is why he so frequently frames skepticism as an impulse or a transgression of language. Cavell’s further point, however, is that a commitment to the ordinary must extend beyond the realm of philosophical debate – precisely because skepticism so extends.

According to Cavell, Shakespeare and Rohmer both investigate the ways in which skepticism seeps into the everyday. My sense is that there is an underlying link between the play and the film which tells us something about how we ought to answer the skeptical challenge; this can be unearthed by building upon Cavell’s reflections on the Winter’s Tale in some detail. There, Cavell sees Leontes’ plight as a near-caricature of skepticism’s world-destroying potential. His radical doubt – “whether his children are his” – will cast the world into a worthless, chaotic mess from which it seems impossible to escape. To make Cavell’s discussion of skepticism even more precise, it is worth noticing Shakespeare’s suggestion that Leontes’ doubt is somehow impenetrable. This is confirmed by Paulina’s indictment upon the King’s rejection of the teachings of the Oracle. According to her, he is subject to “a curse” which he cannot be compelled to remove, for “The root of his opinion” is rotten. What does Leontes’ rejection of the Delphic message say about his state of mind? That he would reject an incontestable, absolute truth sent by the Gods is clearly a mark of something going terribly wrong.

By introducing the oracle into the play, Shakespeare is not only highlighting the world-destroying feature of skepticism, as Cavell is right to notice; he is also exploring the extent to which the obsession with rationalization keeps skepticism alive, and is thus inquiring into the kind of relation to knowledge needed to overcome it. This is reflected in the double role that the oracle plays: on one hand, the oracle’s teachings stand for a public, undeniable truth, so that a rejection thereof is irrational. On the other, it is clear that the oracle is itself a magical entity. Leontes’ failure to believe what it says is thus the ultimate example of his anxiety over certainty: he cannot even trust the undeniable because he fails to find an absolute reason to trust it. The upshot is that his world-destroying doubt simply cannot be cured by appealing to rational deliberation, if that means looking for a further, convincing reason to ground knowledge. This expands on Cavell’s idea that our temptation to “a knowledge beyond human powers is unannounced,” woven into the everyday, and in tension with it. The only way to dissolve skepticism, then, is to turn the investigation around. We must find comfort in the fact that our language alone dictates the limits of what we can know.

Then it is no accident that Hermione, once Leontes charges her with the highest crimes, says “You speak a language that I understand not” – and follows it up by saying, roughly, that this language places her in an unknown realm – “My life stands in the level of your dreams.” The realm of Leontes’ dreams, as retrieved from his language, is evoked as a realm in which it is possible to have absolute certainty without any evidence (his certainty in his wife’s infidelity). But isn’t this kind of blind conviction exactly what we demand of Leontes if he is to accept the oracle’s teaching? Why is it a problem in the former case, but not the latter?

It turns out that the difference between these two instances of certainty without reason (blind faith) is a difference in the relation to knowledge that is recommended in either case. Leontes’ eventual return to sanity is facilitated by receiving confirmation that what the oracle spoke of is genuine; namely, that his son and wife really are dead. Crucially, the lesson Leontes takes from this is not that the truth of the oracle’s teachings gives him a reason to trust it in the future. Rather, he learns that the need to look for reasons in order to have certain knowledge is a misguided position in itself. It is, after all, common that our dreams are filled with nonsensical assertions or rules that make complete sense within that realm; there is no use in questioning them. It is only after waking up, remembering them from the framework of our ordinary lives and language, that their nonsense becomes apparent.

We find the ultimate confirmation of Leontes’ reorientation towards knowledge in his behavior leading up to the reveal of Hermione’s statue. The crucial point is that he has no problem following Paulina’s orders when she says that “It is required You do awake your faith.”

Indeed, to her invitation “those that think it is unlawful business I am about, let them depart,” Leontes declares, confidently: “Proceed. No foot shall stir.” The lawfulness of this project comes in again, shortly after he sees Hermione moving; he explicitly declares his endorsement of magic: “If this be magic, let it be an art Lawful as eating.” His previous self, whose destructive desire for reason and certainty may appropriately be entitled an obsession with lawfulness, has clearly been outgrown. The claim, then, is not that Leontes comes to believe in magic after he sees Hermione moving – that’s easy enough for anyone. It is, in fact, his belief in magic that serves as a precondition for their recoupling. He can only come back to Hermione, and she to him, if he is removed from the skepticism which tore them apart; faith is a strict prerequisite. Therefore, the way Leontes wakes up is precisely by reaffirming his commitment to the ordinary, which is dramatized by his coming to believe in magic – a caricature of loosening one’s grip on the need for reason. Leontes’ faith, then, is what moves the plot forward and into the impossible.

Faith and Magic in Rohmer

These additions to Cavell’s reading of The Winter’s Tale prepare the ground for extending his reading of Rohmer’s film. On the topic of having faith, two crucial sequences from the film are 1) Felicie’s reaction to the final scenes of The Winter’s Tale in the theater, and 2) her conversation with Loic in the drive back home immediately thereafter. Cavell wishes to understand why Felicie is so struck by the play, and what it seems to have triggered in her, with respect to her attitude towards her relation to herself and Charles. It is important to note that Cavell sees, in Felicie, a whole array of characters from the play. The fact that these claims ring true is a testament to both Cavell and Rohmer, but the present investigation suggests that the most productive comparison to press is that between her and Leontes; it provides the most natural point of comparison regarding the relation between faith and skepticism.

Skepticism manifests itself in Felicie, Cavell thinks, through her sense that she is somehow inarticulate. Her acts of misspeaking are sprinkled throughout the film, but a recurring one is her having given the wrong address to Charles after their first time together. For Cavell, this particular act of misspeaking “has, with however different effects, the same consequence on her world as Leontes’ madness,” namely that it excludes from their world the one whom they love. The root of this misapplication of language, a lapsus or slip in the Freudian sense, is a kind of mistrust for Charles, reasonable or not; Cavell speculates that this is a “madness or rage she may have for a moment felt at his intrusive and absorbing role in what was her transformation into a mother.” The upshot is that we see, once again, how skepticism requires “the destruction of language,” or the rejection of the ordinary. Cavell argues that the moment she overcomes this skepticism, her moment “waking up,” as we termed it in Leontes’ case, is in her reflection on the trip to the church in Nevers. In particular, it is “her daughter’s witnessing the [image of Nativity]” which causes her to pray, where praying felt more like “a meditation, one in which her thoughts came to her as with a total clarity.” This realization of clarity comes out in the car with Loic, moments after Felicie is taken aback by witnessing Leontes’ interaction with the reanimated Hermione.

For Cavell, the play “enabled her to articulate that she is found, by herself … she will live in a way that is not incompatible with [her and Charles] recovering each other.” But why did the play allow her to do this, precisely? Here, we may reopen the discussion about coming to believe in magic The Winter’s Tale. There, Leontes has overcome skepticism and returned to the ordinary by loosening his grip on necessity; eschewing the skeptical impulse is what allowed him to see Hermione again. On my reading, it seems that Felicie has a shockingly similar moment of coming to believe in the impossible in the theater. Recall how invested she was into what was happening on stage: “When the statue moved, I nearly screamed.” Indeed, Loic quips that he almost screamed himself when she (unbeknownst to her) squeezed his hand in shock. Felicie buys into the play completely – her childlike conviction in the reality represented by the play, call it her belief in magic, is analogous to what Leontes needed to do so that Shakespeare could incorporate the reanimation of Hermione into his story. And, just as belief in magic is a precondition for Leontes’ eventual rendezvous with Hermione, so it is a precondition for Felicie’s rendezvous with Charles.

We get further confirmation of this thesis from her response to Loic’s drab comment that “the play’s not plausible” – she is quick to communicate her recent realization, namely “I don’t like what’s plausible,” spoken with a newly found sense of justification for her way of life. But one lesson Rohmer is teasing out, perhaps, is that it should be no surprise that someone who is so well-read in the history of philosophy would be recalcitrant to the idea of the plausibility of the play. The Winter’s Tale, for Loic, is seen as unlawful in its own right. Such was Leontes’ obsession with reason in the first 3 chapters of The Winter’s Tale. The elegant answer Felicie gives him is “You don’t get it – Faith brings her to life.” The suggestion on the table is that she is at once communicating her interpretation of the play, and describing what just happened to her own self.

By introducing the uncharacteristically magical element of reanimation into one of his comedies, it seems that Shakespeare is asking the reader to consider whether she can give the play itself the benefit of the doubt. Rohmer’s intervention is to tease out the idea of trusting art to provide transformative philosophical value. What the oracle was to Leontes, the play is to us and to Felicie. Shakespeare’s insistence on the benefits of having faith thus occurs on the meta-level. It questions the reader’s own propensity for rationalization and doubt. This sounds a lot like Cavell’s frequent interjections which occur when he makes strong claims about a film espousing ideas that are “beyond anything the film may know about itself.”

The question of trusting magic, represented in this case by the believability or relatability of theater, provides a natural link to Cavell’s reflections on Plato’s Republic. In fact, this chapter provides ample material to supplement the present discussion of faith and skepticism. The frequent invocation of Plato’s work in key moments throughout A Tale of Winter provides some initial evidence to this point – for example, the frequent mention of metempsychosis compared to Cavell’s insistence that this is a perfectionist idea, communicating one’s choosing of one’s life and society. For the present project, it is worth reflecting on an idea that is omitted in that film but is central to Cavell’s thought – the Myth of The Cave.

For Plato, this thought experiment is meant to show how appearances deceive us, exemplified by the cave dwellers’ failure to grasp the difference between the true object and its shadow. If a human life is like life in the Cave, Platonic ideals are meant to stand for the Reality which earthly appearances can only mimic. According to Cavell, then, Plato sees the everyday as “a scene of something like illusion or delusion,” where we see things that are not really there. It seems uncontroversial to suggest that this view shares features with skepticism, insofar as it doubts the truth of the existence of the other or the outside world. Cavell disagrees with Plato, in the sense that he rejects the theory of forms and thus this version of skepticism; he sees, in the Cave, a restatement of the idea that philosophical problems are sometimes caused by our failure to see the conditions of our confusion, i.e. conditions of our language. The prisoners, in turning around and learning of the true reality of the Cave, may be taken as a representation of our turning the investigation inward, reorienting philosophical thought toward the ordinary and thus departing from skepticism.

It is worth connecting Cavell’s idea that learning about the Cave represents a return to the ordinary with his claim that it “uncannily anticipates a movie theater.” By joining these two thoughts, a version of the prior argument seems to reappear – the idea that a belief in magic facilitates a rejection of skepticism, and thereby enables a perfectionist quest for an unattained but attainable self. In this case, it seems that a recommitment to the ordinary (faith in it) is expressed by a belief in the philosophical power of movie magic. The Cave is a depiction of a film screening, in which the viewers know that they are in a theater; but this awareness does not bar them from extracting value from the screening, precisely because they know that to question the reality of the film is to look for certainty where it ought not be looked for. The fact that the viewer is committed to the ordinariness of the situation he finds himself in is part and parcel of his coming to believe in the magic of the film, a precondition for extracting value from it. This extension of Cavell’s idea will also serve to reject Plato’s vision of the arts as doubly illusory, distracting us from the realm of the Real or of Reason. For Plato, since art is contrary to Reason, and since following Reason is the way to a moral life, art must be removed from our lives. The invitation is to reconsider whether art must be seen as an imitation of some abstract higher Reason, or, more precisely, to loosen our need for certainty as represented by Reason; one way to do this is to believe in movie magic, trusting that the arts can be purveyors of genuine philosophical value.

The idea that faith (dramatized as belief in magic) is something very important to a perfectionist pursuit is illustrated perfectly in Cavell’s companion piece to Plato, His Girl Friday. While the connection is quite straightforward, it is still worth mentioning, if only to indicate that this is a trend that occurs in at least one Hollywood remarriage comedy. Here, the idea of magic is embodied in the character of Walter Burns, whom Cavell describes as a magician, magus, or trickster. His wizardry is a personality trait, and it comes in the ways Burns manipulates the world in order to prove his devotion to Hildy. Her coming to believe in this form of magic amounts to her coming to trust this man – this magician – as the one with whom she wants to continue living. The corresponding breakthrough for this remarriage pair, as Cavell points out, is that what changes is their attitude towards the fact that neither will change. The trickster will resume his ways, but that’s what Hildy wants, and – barring the moment of crisis in which she asked for a divorce – always wanted.

Having reflected upon the ways in which perfectionist aspirations interact with faith and skepticism, all three domains come together in a final thought. In the very last part of Cities of Words, Cavell systematizes a list of perfectionist themes from Plato’s Republic. If there is truth to the claims made throughout this investigation, there is a sense in which a belief in magic – represented variously as an acknowledgement of the transformative worth of trickery, theater, film – is a genuine trend in certain strands of the perfectionist pursuit. It seems that this is so because it implies that the skeptical impulse has been surmounted. The root of the disease of skepticism, which we can now safely declare is antithetical to perfectionist aspiration, will have been removed by a dramatic commitment to trusting what seems to be unbelievable. This is not to say that such a commitment is irrational; rather, it reveals a different attitude toward rationality, one that recognizes the limits of our ordinary language as revealing the limits of our thought. If it must, film finds its philosophical justification in its status as a thought experiment, where our intuitions and visions of life are to be stress-tested. It is precisely because of its power to depict the ordinary that it has value for us, as viewers and as philosophers.